Aging Alpines tend to sound like the submarine in James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty:” ta-pocked ta-pocked ta-pockedta. What may be attractive in a daydream becomes embarrassing in real-life when you clatter into a sports car meet and everybody says, without looking around, “Here comes an Alpine”.

The problem is not in your deodorant. It’s in your valve train. Here’s how to bring quiet and respect back into your life. First, throw away the book. Well, don’t throw away the instruction manuals, but know when to ignore it.

The instruction manual says, for clearance, .012 intake, .014 exhaust. Let’s cheat a little. Make that .010 and .012. But that’s not the real problem. Remember your car is a sophisticated British product, with subtle problems that require real understanding. (That’s one reason why you see so few old British sports cars on the road.)

Do the following:

- Get the engine up to normal temperature. An end to the cheating! Drive it around, and don’t do it by idling.

- Adjust the valves by using wire gauges, not flat ones. We are checking valve clearance, not points, and the difference is profound, as we shall see.

- Make certain that the valve you’re adjusting is in a full closed position, which is to say, the lifter is at the opposite side of the high point of the cam lobe. This can easily be determined by following the valve cycles of intake, compression, ignition and exhaust. (We are assuming you know something about the theory of the four-cycle engine before you took the valve cover off. If you don’t, you are now in trouble). Merely find the compression stroke and park the compression at T.D.C., using the timing marks on the damper and timing chain cover.

A neat feature of the Alpine is the little external button on the rear of the starter solenoid that will allow you to jog the crankshaft around with precision. (It’s almost as if the designers knew that the day would come when the valves would have to be adjusted). - Now we get to the magic, which is to measure the real, and not the apparent gap between the valve stem and the rocker arm. This is why it cannot be done with a flat gauge: the valve stems tend to wear a groove in the rocker arm (and thus that rhythmic ta-pockedta, ta-pockedta). This is an exaggerated view of what happens:

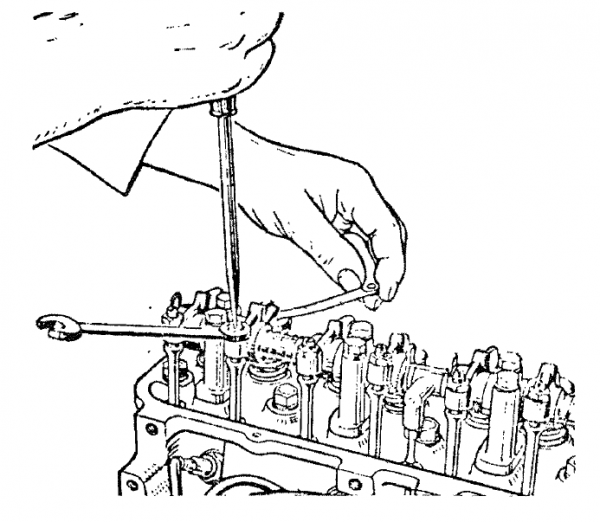

To check clearance, insert a feeler gauge of correct thickness between the valve stem and rocker foot. As shown.

To check clearance, insert a feeler gauge of correct thickness between the valve stem and rocker foot. As shown.

When the rocker clearance is correct the feeler will be firm, but not tight, to move between the rocker and valve stem end, while pushing downwards on the adjustment screw slot with a screwdriver.

To· adjust clearance, slacken lock nut and turn screw with screwdriver until correct clearance is obtained. Tighten lock nut and re-check clearance. Check all valves in this manner, then refit rocker cover.

To measure the real gap requires a wire gauge, which measures the real space between the two metal surfaces. Be careful that the wire gauge does not bear the load from the valve spring. The load would damage the gauge.

We should have said that the engine should not be running during this operation. In case you didn’t understand this, we are sorry about your burnt, bitten fingers.

But, if the operation is done right, you should be able to sneak into the meet next October and run down at least a couple Tiger owners without them ever hearing you creep up from behind.

originally published as The Quiet Alpine – An Almost Extinct Species by Tom Ehrhart in the July 1977 and November 2004 RootesReview

Comments (2)

It is never made clear why one should disregard the instruction manual to change the valve clearance settings from .012-.014 to .010 – .012.

The primary reason to reduce valve clearance is for noise reduction. Experience in 100’s of thousands of miles in my Alpines and others have never produced a burnt valve or other valve or engine problems as a result. Performance difference with efficiency and power are not even noticeable with street driven vehicles.

Why disregard factory instructions? In an old car case, engineering rationale of the time of manufacture tends to be conservative in many areas. I was fortunate enough to spend many hours over several years with John Clegg, one of the two 1725 engine designers. We compared notes about engine design constraints he was tasked to implement (some against his recommendations), typical consumer failures and their causes, differences between the 1592 VS 1725 (1592 much better quality), low oil pressure and Rootes conservative design philosophy that causes it.

There is clear evidence that over time we have been able to improve on the engine durability and power by NOT following suggested manufacture criteria. That is to say we should NOT totally ignore their recommendations. Certainly follow as a reference but be willing to alter if valid engineering information can substantiate improvements.

TT